| Stories | Philosophy Blog | About | Support My Work | Contact |

|---|

Trauma means that my autonomic nervous system got stressed and then didn't fully calm down.

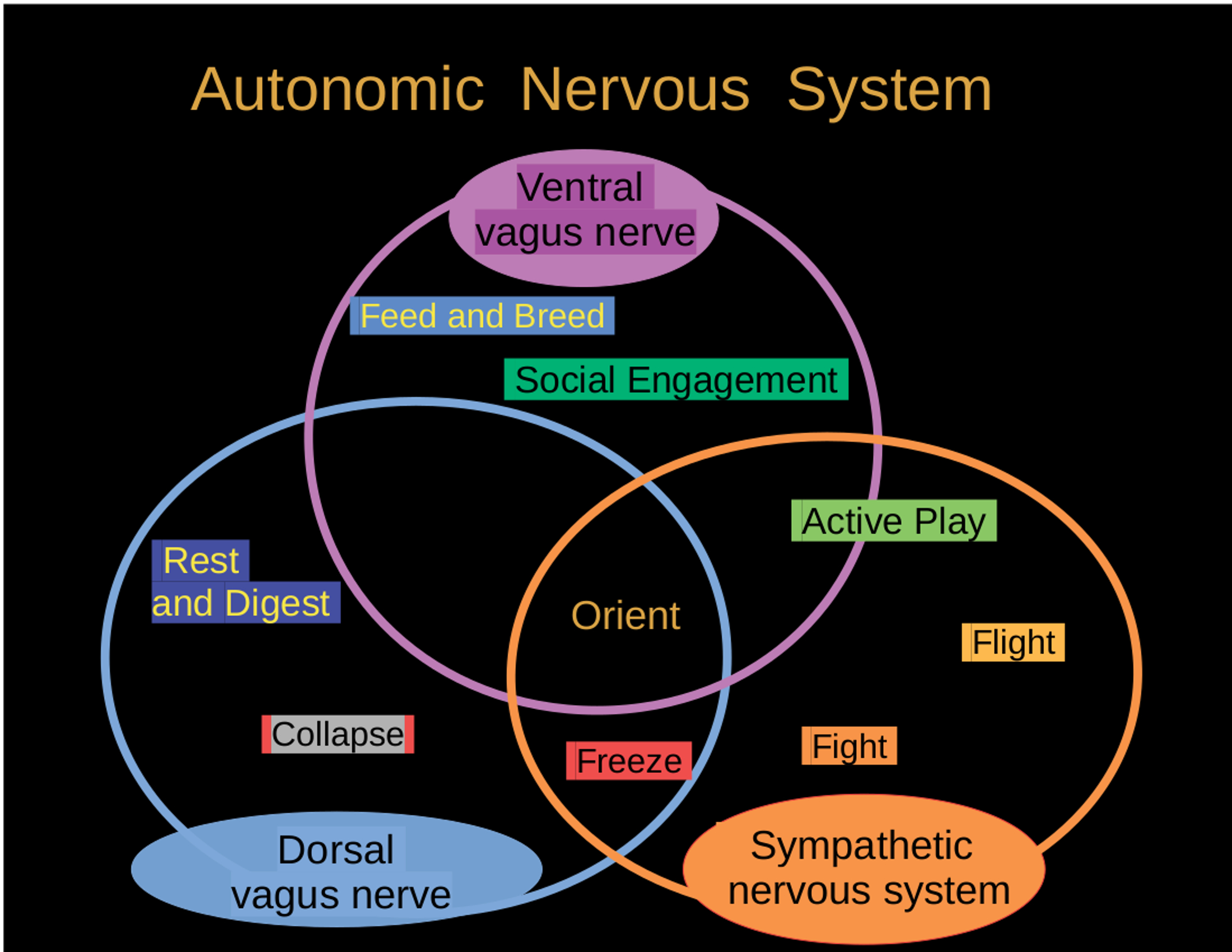

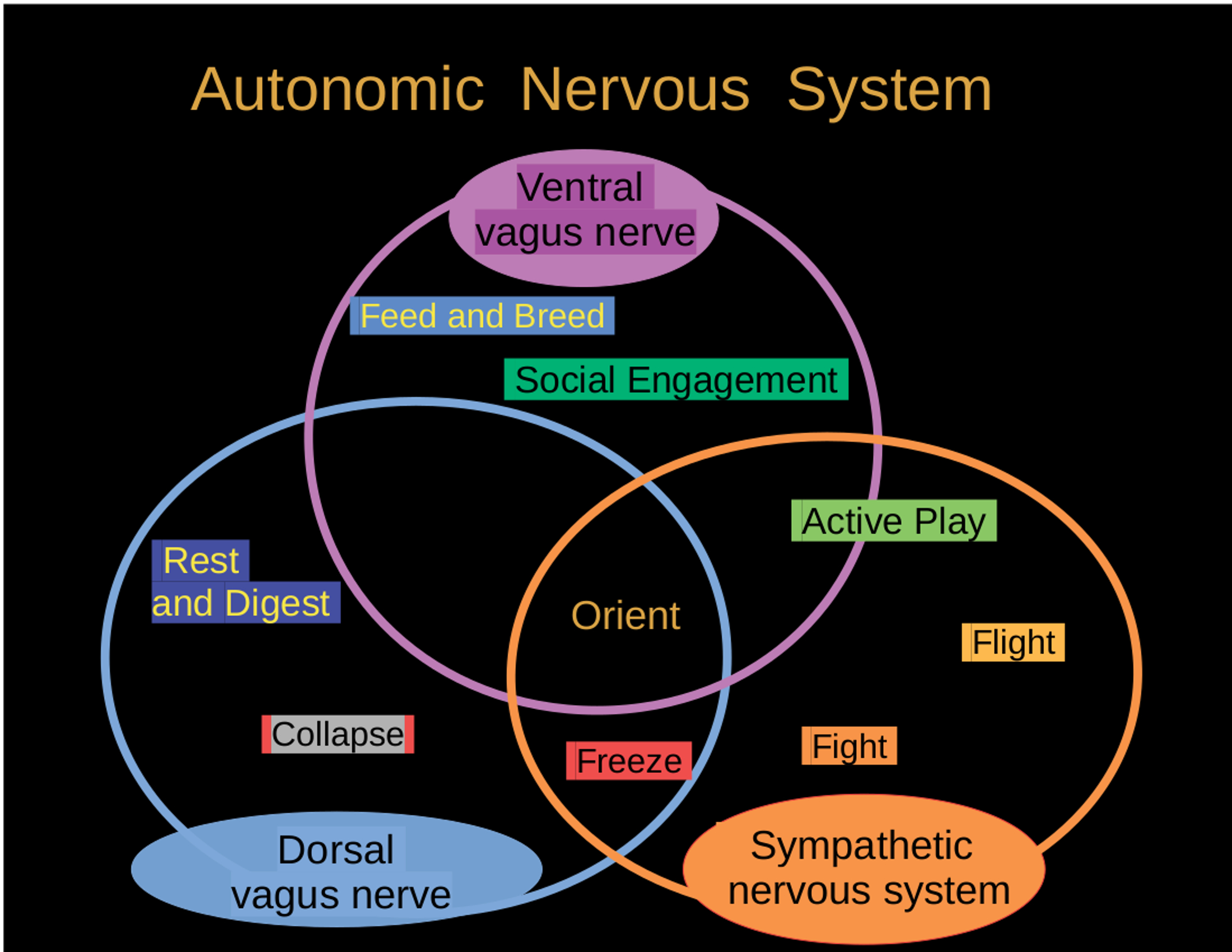

My autonomic nervous system has three branches: the sympathetic nervous system, the ventral vagus nerve and the dorsal vagus nerve. These work in various combinations to produce different responses depending on whether I perceive threat, agency or connection.

My dorsal vagus nerve supports stillness. It's responsible for the calmest state, Rest and Digest, and the state of greatest stress, Collapse. In Rest and Digest, I don't move much because my nervous system says things are okay, there's no need to do anything. In Collapse, I don't move because I perceive no agency, no opportunity to do anything.

My sympathetic nervous system supports movement. When I perceive opportunities for agency and movement, my sympathetic nervous system can activate fairly quickly. If I perceive threat and limited options, I go into Fight. With an opportunity to move away from the threat, I go into Flight. With opportunities for movement and connection and no significant threat, my sympathetic nervous system supports Active Play.

When my dorsal vagus nerve and my sympathetic nervous system are activated at the same time, I have a Freeze response.

When I receive cues of connection and feeling cared for, my ventral vagus nerve activates and shifts me toward states like Feed and Breed and Social Engagement.

When I perceive increased threat or decreased agency, my autonomic nervous system can shift very quickly to states of higher stress. Shifting to states of lower stress takes longer, and my body often needs to go through a physical discharge to shift to a state of lower stress. Since trauma is my nervous system holding on to stress, discharge is often a part of resolving trauma.

Some common forms of discharge are crying tears, laughing, shaking, yawning, spontaneously stretching and adjusting my posture. There's no point forcing or faking discharge. I do practice noticing it and supporting it when it happens.

Something I can do deliberately to help my autonomic nervous system calm down is to activate my Orienting response. I turn my head and look around for something that sparks a sense of joy, curiosity or connection. Then I pay attention to the raw sensory input, not just my linguistic thoughts about it. Reading words isn't orienting. Instead, I can notice the colour and texture and font, and the wiggling motion of the pencil as I write.

Wild animals orient all the time, and they rarely get traumatized. Even if a deer goes into a Flight response, as soon as the threat is gone it orients, shakes and goes back to the Feed and Breed state that it was in before perceiving a threat.

As a modern human, I can't always do that. I instinctively want to learn from my experiences, and I want my family and friends to learn from my experiences, especially when they're stressful ones. If a threat is ongoing, or if I don't have an opportunity for meaningful debriefing when it's over, then part of my nervous system takes on the task of remembering the stress until I can share the story, and disconnects from the rest of my nervous system, which largely forgets about the stressful situation in order to get on with life.

Trauma can range from very severe to barely noticeable, depending on how much of my nervous system is occupied with the memory of stress and how completely it disconnects from other parts.

We haven't evolved to maintain this disconnection for more than a few days. My instinct expects my family and friends to be available and keen to join me in learning from my experience. If have no opportunity to integrate a stressful memory for months or years, the part of me that's holding the memory and waiting to tell the story gets confused and impatient. Then it creates symptoms to remind me that there's still learning to be done to integrate the stressful memory. These symptoms can be almost anything. Here are some typical ones:

Re-enactment means I unconsciously or compulsively recreate the situation that was traumatic. Unfortunately, the re-enactment itself can be retraumatizing, especially if it causes harm to myself or others.

Given adequate support and resourcing, anyone can theoretically recover from any amount of trauma. However, not everyone has adequate support, and there's no single resource or strategy that works for every traumatized person. I've had to invent a lot of strategies for myself. I find it helpful to work from multiple angles:

Getting needs met is the most basic. I do my best to meet connection needs as well as physical needs and needs for agency, meaning, learning and contribution.

To shift any part of my brain to a different autonomic state, I practice orienting. I can practice orienting almost anywhere and anytime, for a brief moment or for minutes or hours. I find it helpful to go outdoors and orient to my natural environment, including where the familiar plants are, what the birds are saying, which direction the wind is blowing and which mushroom has been eaten by slugs. I happen to have access to natural environments with minimal threats, where my skills and knowledge enable me to orient to both connection and agency. I realize not everyone has the same access, or skills, or knowledge. Some people find it easier to orient to connection with a familiar human, or to the sight of a beautiful object in a comfortable indoor space.

Any opportunity for movement, from martial arts to dancing to stepping out for a walk, can help me shift out of Freeze or Collapse into states of lower stress. Moving my body can be a form of discharge that satisfies my Fight or Flight instinct. When the movement feels complete then I can orient to opportunities for connection or rest.

Using my story for learning can be really powerful. On the other hand, unlike meeting needs and shifting states, it involves recalling memories of stress, which can be retraumatizing. I find it works well when I have someone with me who is willing to really pay attention and learn from me, and when I am able to describe my stressful experience in ways that they can understand. I'm learning to interrupt the storytelling for frequent, brief sessions of orienting to avoid retraumatizing myself.

Working with parts of my brain and getting them to reconnect with each other has been fascinating, helpful and challenging. It can compliment getting needs met, orienting to connection and agency, movement and having someone available for meaningful debriefing. My first method for supporting communication between parts of my brain was to write with my two hands taking turns with the pencil. Each hand represented a hemisphere of my brain, and they took turns expressing themselves. That was wild.

In conclusion, I understand trauma as a disconnect in my nervous system with some parts focussing on a stressful memory and trying to integrate it, or waiting for opportunities to integrate it, while other parts ignore the stressful memory and focus on day-to-day life. When I don't have adequate resourcing to process my trauma, I can still work on getting my needs met and shifting my autonomic state. When I have more resourcing, I can also integrate the memories by using them as sources of learning for other people or for myself.

The TL;DR on Trauma by Tamias Nettle is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International